Teresa, a 52-year-old with a solidly middle-class job in the healthcare industry, recently separated from her husband. At the time, the couple lived in Encinitas, in a large home they bought in 2010 for $450,000. When interest rates plummeted, they refinanced at less than 2.5 percent with only 13 years of payments left. Each month, the mortgage, the insurance, and the money they set aside for real estate taxes came to $2,900 between them.

But now, the market has shattered Teresa’s financial calculus. Even after she and her husband sold their house and split the profits, affording to buy again seems impossible. She is currently renting, but with the San Diego rental market being one of the hottest in the country, she found slim pickings. Teresa is paying $2,000 a month to live in a small, one-bedroom accessory dwelling unit (ADU) in North County, without an oven in the kitchen, behind a friend’s house—and she counts herself lucky. On the open market, she says, that unit could rent for as much as $3,300.

And that cost is no outlier. Teresa pulls out her phone, bringing up Zillow listings from around San Diego County: $1,650 a month for a 250-square-foot studio, $2,200 for a 600-square-foot one-bedroom, $2,350 for a 350-square-foot studio.

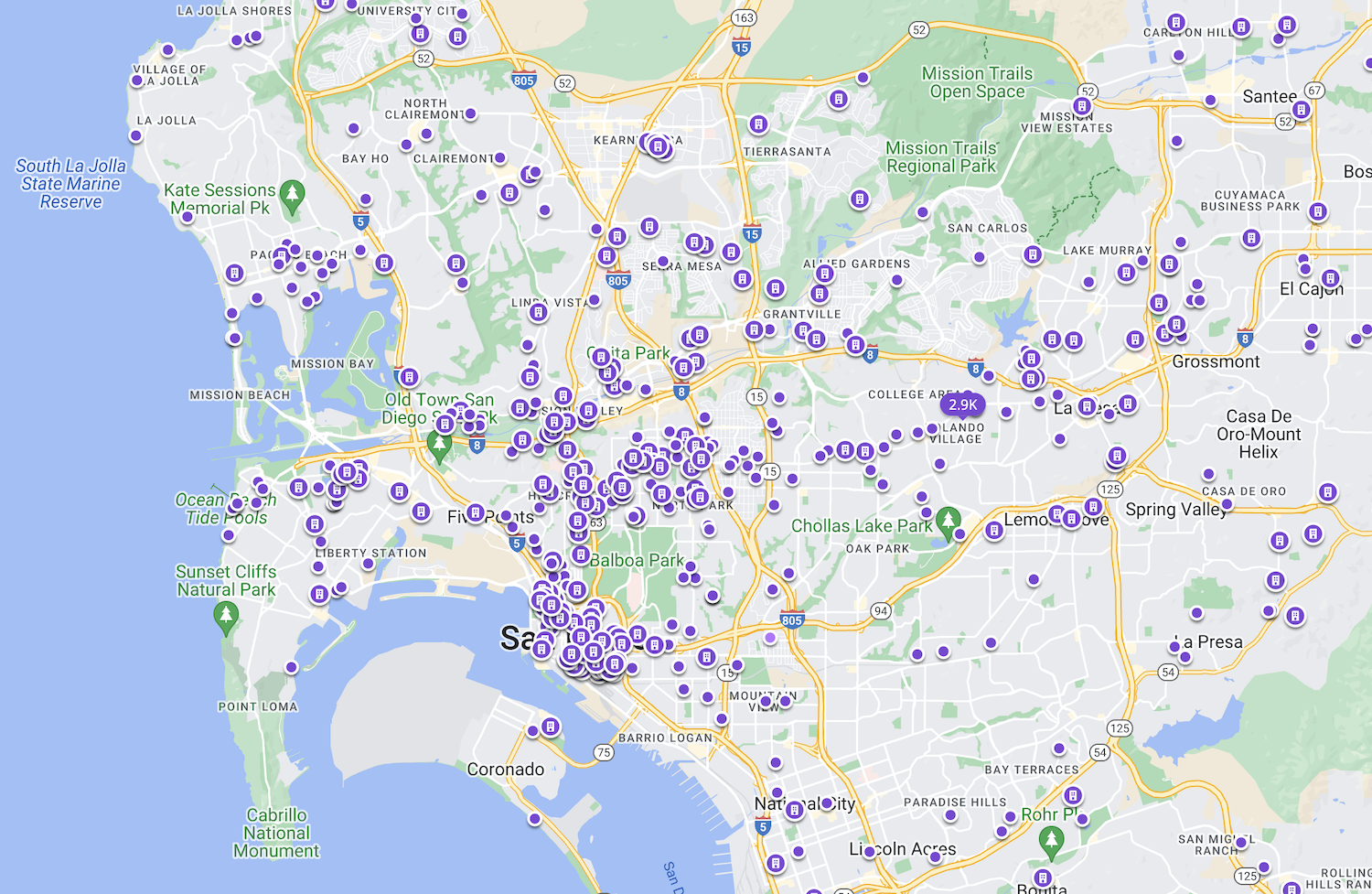

San Diego is at the forefront of California’s affordable housing crisis, and California is at the forefront of a national housing shortage—US Census Bureau data shows that, countrywide, the home vacancy rate is at 0.8 percent, less than half of what it was a few years ago. A recent report from Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies found that over 12 million households were spending more than half of their income on rent. And, when new apartment buildings are constructed, developers increasingly build for higher-income renters, leaving working- and even middle-class tenants unable to get a foot in the door.

In part because of the housing crunch, more than 800,000 Californians left the state between 2021 and 2022, according to the Census Bureau. Despite hundreds of thousands of new arrivals, California ended up with a net loss of 342,000 people, not far shy of one percent of its entire population.

In the face of calamitously high rents, those who remain in San Diego are taking to Facebook, Craigslist, and other online venues, desperately trying to sell themselves—their personality traits, looks, and financial stability—as would-be roommates.

Sergio Castro-Gutierrez, 36, has found it impossible to qualify for an apartment in North County, despite working 50-hour weeks.

For Sergio Castro-Gutierrez, a 36-year-old chef originally from Barcelona, Spain, finding housing is more complicated than simply picking a roommate. Recently separated from his wife and desperate to stay in the North County area to remain close to both his young daughter and his place of employment, he finds that, even working 50 hours a week at the Omni La Costa Resort, he still isn’t earning enough to pass muster with landlords when he applies for an apartment.

There are available rooms in houses that he could afford, but, he adds, who would feel safe bringing their 5-year-old daughter to stay in a house with strangers? The one-bedrooms that he has found in North County range in price from $2,600 per month up to $3,300, far beyond what he can afford, given he only makes between $4,000 and $4,500 each month, part of which goes to help support his ex-wife and daughter.

Landlords want proof of income three times the rent, meaning that Castro-Gutierrez would have to earn almost double what he’s making to be in the running for an apartment. While he searches, he is living with his ex-wife’s uncle, but Castro-Gutierrez says when the uncle renovates the home in a few months, he’ll have to find his own place. As much as Castro-Gutierrez likes San Diego, “it’s hard,” he continues. “You’ve got to have two jobs to survive if you’re by yourself. And then, you cannot even enjoy your place, because you’re always working.” Many of his friends have migrated to Texas and Arizona for cheaper digs.

Mishele Stead, 54, will soon be forced from her Golden Hill home so developers can build luxury apartments.

Mishele Stead, a 54-year-old housing navigator for a local nonprofit that helps formerly incarcerated people find affordable residences, has lived in the same rental unit in Golden Hill for the past decade. She pays $2,000 monthly for her two-bedroom, one-bath, which is already more than half her $24.92-per-hour income. However, the property recently sold, and the new corporate owners want to knock down the building and construct luxury apartments. Stead is terrified that, once she gets the 60-day notice to vacate, she will not be able to find an affordable unit to rent.

The data provides ballast for her fears. Last year, Zillow reported that San Diego was now the nation’s third-highest-priced rental market, just behind New York and San Jose. Realtor.com recently estimated that San Diego would have the country’s fourth hottest real estate market this year, with demand and prices continuing to increase. High purchase prices have a ripple effect into the rental market as well, driving up the cost of renting even more.

Stead is no stranger to squeezing the juice out of San Diego’s housing stone for her clients—she frequently places them two-to-a-bedroom in tiny apartments with the most basic kitchens, equipped only with hot plates. But as she’s begun looking for herself, she’s stumped: Her wages have been increasing by three to four percent annually in a real estate market where rents have been growing by at least seven to eight percent yearly.

As a result, the $2,000 she currently spends on a two-bedroom will likely get her only a studio once she has to move, a realization that has left her somewhat bitter.

Stead at home with her pets.

It’s not as if the city and state officials don’t realize there’s a problem. Over the past few years, several legislative efforts have been put in place to protect renters and first-time home buyers struggling to enter the overpriced ownership market. California’s $300 million Dream for All program helped lower-income buyers with their upfront costs, fronting some of the down-payment monies needed in exchange for the state having part-ownership in the property. However, so many people applied that the program ran out of funds within days of going online.

Last year, to address the housing crunch, legislators passed AB 68, allowing homeowners to build one ADU and one junior accessory dwelling unit on their lot, thus effectively rendering single lots into potential triplexes and working around at least some of the zoning restrictions preventing the development of high-density housing. And this year, another bill, AB 1033, has been introduced, allowing homeowners to sell those ADUs separately from their main property.

In the long run, those reforms might add some affordable housing stock to the market and could open up more ADU rentals at affordable prices. So, too, might efforts to modify the California Environmental Quality Act, which has been abused in recent years by opponents of denser housing projects who sue under CEQA to stop any developments in their neighborhoods. But in the short term, the crisis shows little sign of easing.

The Tenants’ Protection Ordinance, signed by San Diego’s Mayor Todd Gloria in May 2023, expanded protections against eviction without just cause. Tenants who are evicted through no fault of their own are entitled to two months of rent relocation assistance (seniors and those with disabilities get three months). The ordinance also limits the circumstances in which landlords can use an upcoming renovation as an excuse to kick tenants out. Yet, these measures haven’t addressed the more significant issue: demand exceeding supply and hugely driving up the cost of renting in the region.

PARTNER CONTENT

Since 2019, California has limited annual rent increases to 10 percent for existing tenants. Still, it doesn’t have a statewide rent control system to restrict increases when there is a turnover in occupancy. And while several cities, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento, Berkeley, and Santa Ana, have, with mixed success, attempted to create local rent control ordinances, to date, San Diego hasn’t moved in this direction. And renters are bearing the cost.

Stead, a devoted outrigger canoeist who participates in competitions up and down the coast, fears that this year, she’ll have to forgo her hobby and instead put all her available money into rent. “You’re losing what affordable housing you have currently to demolition and new development,” she says. “I feel scared now that I’m already priced out of the market.”