There’s a kissing sound coming from the Mesa College Art Gallery. Its source: a red-lipsticked mouth, smooching the air on a television screen bedecked with tulle, rose petals, a white satin veil.

“I was really trying to break the myth of marriage,” artist Grace Gray-Adams says. “I see the focus [of modern weddings] being more on the money and the flash than the sacrament of marriage.”

A lifelong San Diegan, Gray-Adams was one of the first students to attend the then-brand new Mesa College in 1964. She’s now 77, and the very same school where she conducted early artistic explorations is hosting a selection of works from across her career.

Glimmers of Grace, on view through Oct. 26, certainly exposes the cracks in some of our most dearly held cultural institutions—not just weddings and marriage, but religion, too. Gray-Adams grew up Catholic, and the Catholic imagination pervades her work, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Courtesy of San Diego Mesa College

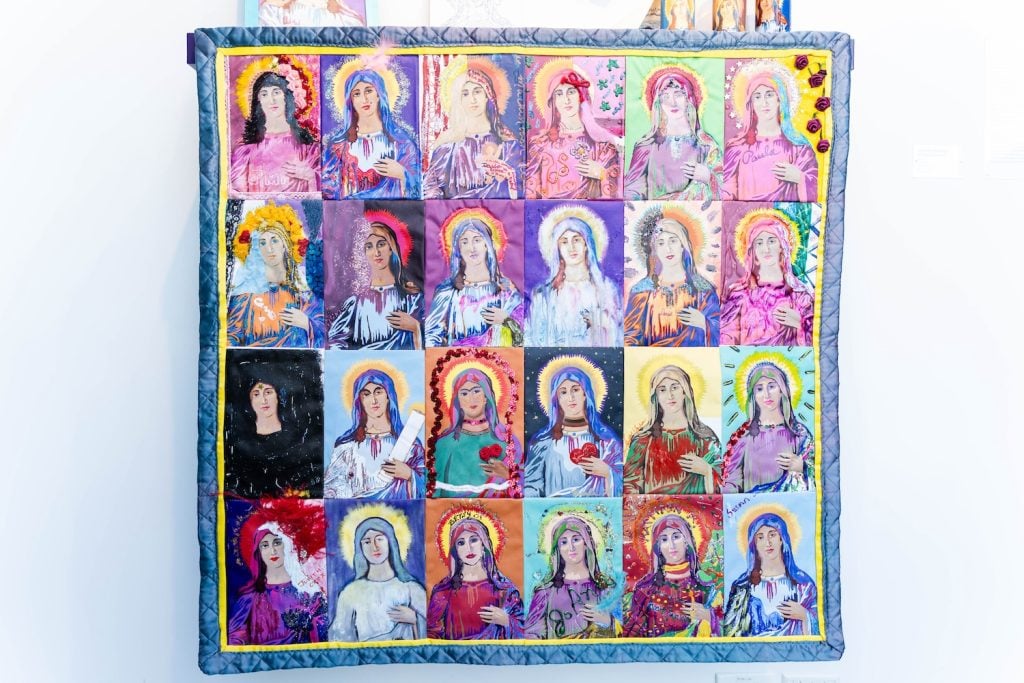

On the gallery walls, the Virgin Mother turns technicolor in a Warholian quilt composed of paint-by-numbers sheets bearing her image. Gray-Adams created the piece in collaboration with other women, friends and family members whom she invited to varnish their own version of the Virgin.

A more sobering piece deals with sexual abuse in San Diego’s diocese. A former member of the Holy Spirit parish in Oak Park, Gray-Adams has childhood friends who were part of the landmark 2007 settlement paid to those abused by clergy members in several local churches. She honors those impacted with an altar (on it sits a communion cup bearing the words “Bless them, Father, for you have sinned”) and the work Entrails, in which bulbs of sheer black fabric hang from the ceiling, stuffed with shredded photographs of the survivors. As the name suggests, the piece is visceral, stark in the presence of the other works’ soft pinks and filmy shades of white.

Courtesy of San Diego Mesa College

Mere feet away, a video installation of women frolicking in vibrant, rainbow-hued veils plays, the veils themselves hovering like ghosts, suspended from the ceiling in tribute to one of Catholicism’s most famous intellectuals, Saint Hildegard of Bingen. Gray-Adams is comfortable allowing these tensions to play out across the exhibition, celebrating the beauty of the Catholic legacy at the same time that she confronts its horrors.

“[Catholicism] is my vocabulary,” she explains. “I don’t have to throw it away because I disagree with a lot of the things that go on in the church.”

Indeed, a key element of Gray-Adams’ distinct perspective is her ability to see the value in what others might toss out—even dryer lint. The material pervades the exhibition, arranged into portraits of “sacred yonis” and twisted into grayscale lilies. Gray-Adams created the floral lint sculptures while in graduate school. She was in the midst of a divorce and caring for her ailing mother-in-law. Meanwhile, she says, “my husband was off in Boston meeting his girlfriend’s family. Do you see how I felt insignificant? Like if I got a divorce, I was no longer a person? But [the dryer lint] proves that I was here.”

Courtesy of San Diego Mesa College

Presented as a record of Gray-Adams’ existence, the lint becomes sacred. Pieces of it sit beneath a microscope and a magnifying glass, asking viewers to study its intricacies, to bear witness. The fuzzy refuse contains bits of Kleenex from her children’s pockets, the foxtail that once clung to her family’s clothes, even strands of hair from her mother-in-law—vestiges of her time on earth. The “wedding dress,” its lips smacking comically, is absurd when quietly juxtaposed with women’s work in one of the most fundamental but undervalued domains: the home.

In writing about art, I hesitate, always, to be prescriptive about who an exhibition is “for”—after all, haven’t I (a queer, Latina woman) found resonance and comfort in so many works by straight, white men? And haven’t far too many works by underrepresented voices been ignored by people who thought they could never relate? Grace, as Gray-Adams defines it, has the capacity to touch us all.

But Gray-Adams is a feminist artist. Her work is—unapologetically, courageously—about the experience of being a woman. Its pressures and wounds, its camaraderie and joys. I walked through the exhibition with two other women, each of us a generation apart. We found ourselves drawn into its narrative, adding our own stories. We spoke of our mothers, my colleagues’ children, the romances that had moved us. The exhibition is one that invites women to be honest with each other.

Courtesy of San Diego Mesa College

Tucked behind a wall in the gallery is a bed dressed in white sheets. A hole in the bedclothes reveals another mouth, then another—a hidden screen flashing a series of rouged lips, woman after woman telling the story of her wedding night.

I’d relay a few of them, but the truth is that I didn’t catch all the words. My companions and I were talking, too, recalling the religious and cultural mandates of our youth, the way they shaped our perceptions of sex.

PARTNER CONTENT

We stood in a loose semicircle in the low light of the makeshift bedroom, our own lips moving.

View Glimmers of Grace at the Mesa College Art Gallery through Oct. 26. The artist will host a talk from 5 to 6 p.m. on the exhibition’s closing day.