You land in Oaxaca City with your husband and twins. Your friends are posting pics of the beach— the Bahamas, Cabo, Puerto one-thing-or-another. You panic. Why did you choose Oaxaca? You’re landlocked with two six-year-olds. This could go sour.

No, you chose this vacation for a reason. Mole! Mezcal! Art! Yes, you remember now—you are here to immerse your family in centuries-old crafts and culture. You do not need Spandex and seashells. You can do more than sand and waves.

You would have stayed at Hotel Escondido or Quinta Real or Hotel El Callejon, but you do Airbnb now to get extra bedrooms. Again, twins. You wonder for the 1,000th time since having kids why hotels were built to torture families.

A flight of eight different corn-based drinks at La Atolería

To fortify yourself before exploring the Ruta Magica de las Artesanias (or “Magic Route of Crafts”)—a route made up of small towns surrounding Oaxaca City that specialize in different crafts like weaving, embroidery, and ceramics— you eat all the things. Tlayudas from Chili Guajili, pan de elote from Boulenc, huevos divorciados from Pan:Am, paletas from Mezcalite POP!, a flight of eight different corn drinks from Atolería.

You could try one of many cooking classes, like the one from La Cocina De Humo, but you ease yourself into your workshop-laden visit by taking a chocolate class hosted by Chimalapa Cacao. You learn Oaxaca is home to more than 20 different cacao beverages, some made entirely of foam. You roast the cacao beans on a comal (a smooth, flat griddle), peel off the brittle skins, and grind them with spices. You mix the resulting powder with water using a specialized wooden wand called a molinillo. You have an epiphany: Any place that has a specific chocolate utensil is the Right Place.

Diego Armando Contreras measures the perfect ratio of chocolate to water for the quintessential Oaxacan hot chocolate during a workshop at Chimalapa Cacao

“We want to teach people that chocolate is more than candy,” explains Diego Armando Contreras, biologist and one of the resident chocolate experts.

You feel bad for all the people snorkeling right now. They are not sipping chili chocolate.

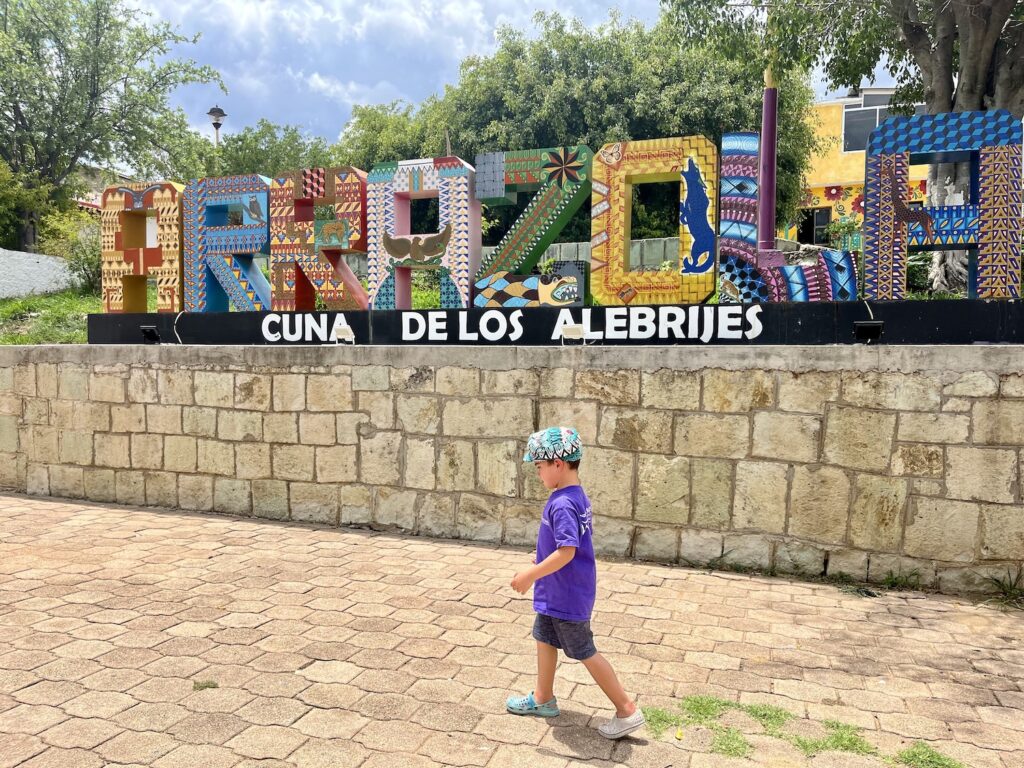

The next day, you take a 20-minute drive to Arrazola, a small town that specializes in alebrijes, whimsical creatures painted in bright, intricate designs. The godfather of alebrijes was Pedro Linares, who is said to have hallucinated the elaborate, animalistic beings during feverish visions he had in the 1930s.

Instead of Linares’ papier-mâché, Manuel Jimenez of Arrazola started making alebrijes out of hand-carved copal wood. You visit the workshop of his grandson, Armando Jimenez. Armando’s wife holds up a log, saying, “We bring out the animal that’s inside.”

You want active participation, so, of course, you sign up for an alebrije painting class. It looks easy to paint. There are lots of colors and dots and ovals and stripes. You sit around a table, feeling confident with 50 different pigments and a bare armadillo. As you swab your paintbrush in hot pink and flub an oval, you build a deeper appreciation for the art form and for the skill it takes to paint even one perfect circle.

Snapshots from Oaxaca

You remind your kids that travel is heart-opening and humbling and they say, “Where’s the green? No, not that one,” and “Why does paint taste so bad?”

You need adult time, so you finagle a sitter recommendation from your Airbnb host and go to Crudo for dinner. The chef, Ricardo Arellano, who once lived and cooked in Escondido, CA, helms the Japanese-fusion establishment. His food makes you emit moany noises, but it’s not weird, because it’s doing that to everyone.

You overhear a guy four stools down talk about a ceramic studio a few towns away—a 76-year-old man who is blind creates sculptures using red clay that his family digs up in nearby fields.

Sculptor Don José Garcia, who is blind, molds clay at his workshop, Manos Que Ven

Two days later, you are in a car with the guy four stools down, driving to San Antonino Castillo Velasco to visit the man’s workshop, Manos Que Ven (“Hands That See”).

Don José Garcia’s signature pieces are faces on pots. Most look like his wife and sport her iconic forehead mole. He tells you that “love” is his inspiration and that he calls his wife “Princesa Magnolia Pechos de Oro” (or “Princess Magnolia Golden Breasts”). You wonder why your husband hasn’t come up with a cute nickname like that for you. If he were a sculptor, would he lovingly recreate your hairy upper-arm mole or your abnormally tiny and thick pinky toenail?

Assistants teach you Don José’s process by allowing you to attempt to form a visaged vessel, which they will fire for you to take home. They teach your kids, too, but instead of a vessel, one makes a blob with one whole that she tells you can both eat and poop. You pretend not to hear or see her demonstration.

You don’t have time to visit all the towns that specialize in clay, but there are multiple nearby with workshops to tour and places to get your hands dirty. One town is San Bartolo Coyotepec, which is famous for its black pottery. Yet another, Santa María Atzompa, is known for clay works fired in a ubiquitous algae-green glaze.

Before heading home, you manage to fit in a few more big experiences. You hit Hierve el Agua, a highly photogenic and swimmable mineral spring, before arriving at Teotitlán del Valle, a town known for tapestry.

Casa Textil Arte Zapoteco is a cooperative of 65 families. Alfredo, your host, tells you that his ancestors moved to this valley hundreds of years ago. They had fled the Aztecs, who had built quite a reputation for painting people indigo and sacrificing them to weather gods. The only thing the people of Teotitlán want in indigo is their beautiful Zapotec rug designs.

Adding acid or citrus to powdered cochineal bugs produces a rich blood-red dye

You see a demonstration about the dyeing process— how pecans make brown, moss makes green, cochineal insects make red—and have an option to sign up for more intensive natural dye courses.

You and your offspring are satisfied by the quick version. Alfredo dries the cochineal bugs, crushes them into a powder, and uses various methods— like lime juice or baking soda—to rehydrate them into different shades of red, anything from rosy pink to dark crimson.

As you leave, your son asks over and over again, “Why did the sun god want dead people?”

The five-mole tasting at Los Danzantes

For you, the most magical part is driving with a guide to the town of Cuajimoloyas and going mushroom foraging in the northern Sierras. You find amanitas, russulas, and boletes hiding under pillows of pine needles and bring them to a tiny restaurant, El Mirador, for the chef to transform into traditional fare. Your favorite is the amanitas cooked in a packet with mayonnaise, Oaxacan cheese, and epazote. You are sure you will crave this taste (and moment) for the rest of your life.

In between your workshops, you’ve managed to eat at Casa Oaxaca, Adama, and Criollo and do the very worthwhile five-mole tasting at Los Danzantes. Oaxaca is the culinary capital of Mexico, after all, so you need to do your due diligence. You take a five-hour market tour in Central de Abastos. You put it all into your mouth: huaraches, memelas from Doña Vale, tesajo, tejate, habanero chapulines, pulque, squash-blossom empanadas. You realize you have not felt hunger for about eight days, and you are proud that you haven’t let that stop you.

Someone tells you about a cocktail. They say, “You must have this cocktail before you leave.” You go to Selva to get the drink made with hoja santa, poblano liqueur, and mezcal and garnished with a roasted Oaxacan cheese ball. They don’t allow children in the bar, but they happily serve you the drink outside. People were right—this is divine. It’s bright, fresh, novel, creative, deep, and delicious. It’s Oaxaca in a coupe glass.

The namesake drink at Selva, a sweet second-story cocktail bar, comes garnished with a roasted ball of Oaxacan cheese.

On your last day, you develop stomach issues. You are in the fetal position, but you’re an optimist; you brag about your new ability to turn any food into water.

You are not sure what the kids have processed from this trip—you briefly think about the beach, the waves—but then one taps you on the shoulder. “I love Oaxaca,” she says. “Can we come again next year?”

You picture those poor suckers with their sticky snorkels, sunburns, and sandy skin crevasses, and you know it for sure now—you nailed this vacation.

Oaxacan Cuisine Mentioned

Chapulines

Deep-fried or toasted grasshoppers seasoned with lime, chile, garlic, and salt.

Epazote

A leafy herb sometimes called “Mexican tea.” Powerful and medicinal in flavor, it has notes of citrus, oregano, and anise.

Hoja santa

A leafy, aromatic herb with flavors of eucalyptus, liquorice, mint, and tarragon. Its name means “sacred leaf.”

Huarache

Masa (cornmeal) dough filled with refried beans and formed into an oblong shape that resembles the leather sandal that shares its name. It’s then fried and crowned with salsa, meat, onions, potatoes, cilantro, and queso fresco.

Huevos divorciados

“Divorced eggs.” Similar to huevos rancheros, this is two fried eggs served over tortillas, but one egg is covered in green salsa and the other in red salsa.

Memelas

A small, oval-shaped, fried or toasted masa cake. Typical toppings include black beans, salsa, shredded cabbage, mole negro, guacamole, and cheese.

Mole

A name for several different sauces, typically containing chiles, fruits, nuts, and spices. The most famous, mole negro (“black mole”), is made with chocolate.

Paleta

An ice pop. Creamier milk-based paletas come in flavors such as horchata and vanilla, while water-based pops are made with fresh fruit.

Pan de elote

A corn cake. Made with sweetened condensed milk, it’s sweeter and moister than American corn bread, with a bread-pudding texture.

Pulque

A milk-colored alcoholic beverage made by fermenting agave sap. Said to be North America’s oldest fermented drink, it’s tangy, like buttermilk, though a version called pulque curado is sweetened with honey and fruit.

Tejate

A non-alcoholic beverage made with roasted corn flour, fermented cacao beans, cacao flower, and the toasted seeds of a sweet-and-savory fruit called mamey sapote.

PARTNER CONTENT

Tesajo

Thinly sliced, salt-cured beef, usually made from organ meat or flank steak.

In Oaxaca, it’s often served with tlayudas (see below) and radishes.

Tlayuda

A large, crunchy tortilla, traditionally topped with refried beans, pork lard, lettuce or cabbage, avocado, meat, Oaxacan cheese, and salsa. It looks like a cross between a pizza and a tostada.