Mario “OG” Lopez walks me through a maze of display cases: tapes, old photos, vintage DJ equipment. It’s all part of the New Americans Museum’s Beyond the Elements exhibition—a San Diego hip-hop retrospective and passion project he curated.

“There are four elements in hip-hop, and the vision of the exhibit was to go ‘beyond the elements’ and embrace the multicultural roots that are a huge part of hip-hop,” he says.

Through airbrushed jackets, throwback posters, and VHS footage, those four elements—deejaying, emceeing, graffiti art, and breakdancing—mix together at the Liberty Station showcase, telling the story of rap’s local beginnings.

“These are my friends,” Lopez says. “I’ve always wanted to show the art.” It’s a short answer to a long question about inspiration and ideas, about what goes into putting something like this together.

As we continue through, he points out a face. “There’s Zodak,” he says, gesturing toward a framed, black-and-white Tribal ad featuring the legendary local graffiti artist holding a name plate. Highlighting his own work (he’s a graphic designer), Lopez motions to the cover of Aztec Tribe’s cassette single Diego Town. The artifacts are a dense tapestry, a timeline four decades long of rappers, breakdancers, DJs, and painters, spread across two rooms.

It would be easy to recognize the players if this were New York or LA, but rap stars aren’t traditionally plucked from around these parts. There’s talent, for sure; however, most of it has had little influence outside of SD. That’s to say that this is a self-contained history, based on a homegrown ecosystem held together by storytellers, smooth talkers, and colorful personalities.

There’s no defining sound or even a single approach. Aztec Tribe carved out a lane as Chicano rap pioneers in the early ’90s, while San Ysidro’s Legion Of Doom (LOD)—who are featured prominently throughout the exhibition—worked their tag-team, Run-D.M.C-like chemistry into a formula that repped South Bay.

And while the vocalists were manipulating rhymes, local dancers were adopting the movements and body contortions of hip-hop’s B-boy element: a choreographed set of ticks, spasms, and spins that, in our neck of the woods, was part West Coast pop lockin’, part East Coast footwork. They’re represented, too, in the exhibit.

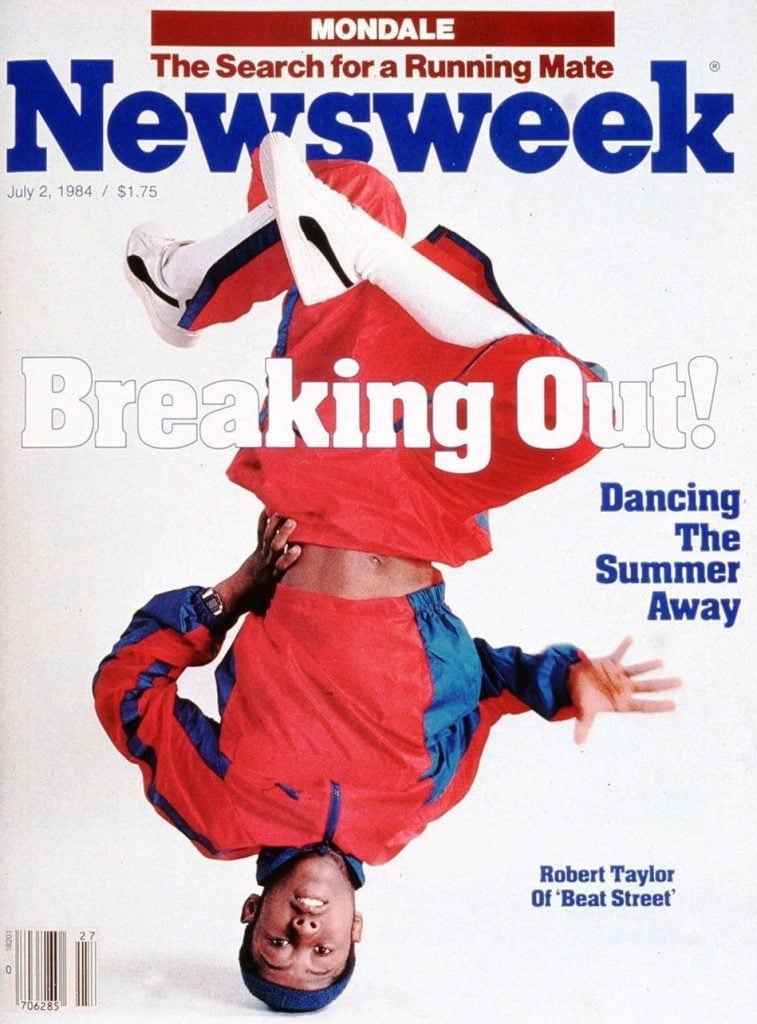

A wall marked “80’s Breakdance Era” shows off hand-drawn flyers and pictures of teenagers frozen mid-routine, rocking on linoleum. Inside a glass square stands a July 2, 1984, copy of Newsweek magazine that reads “BREAKING” in bold, white letters. And resting near the top sits a black medallion from the Universal Zulu Nation, an international awareness group and official fraternity of hip-hop—a true mark of legitimacy. The pieces speak for themselves. The hometown B-boys were the real deal.

That’s how Lopez got his start: managing a group of breakers called the Floor Masters. “My mom’s house was kinda like the home base,” he says. They were unique on their block, but the culture reached beyond his ’hood. It wasn’t until he and his squad ventured past their side of town that any of them realized breakdancing was everywhere.

“We didn’t know that it was happening in other neighborhoods,” Lopez says. “So, when we would go and perform at Balboa Park or something and put out the hat to make money … then [we] had other crews coming and [trying] to battle.”

Just as hip-hop in NYC was a byproduct of its boroughs (even though it started in the Bronx), rap’s local vernacular differed depending on its enclave. Aztec Tribe was based in Spring Valley, while Mario and the Floor Masters grew up in Sherman Heights.

From the county’s eastern edge to its downtown hub, there’s an extensive history documented in Beyond The Elements. The exhibit captures our rich heritage, one that’s worth exploring. And, as a narrative, this isn’t a nostalgia exercise or a trip down memory lane. Instead, it’s a commemoration, a nod to the hometown trailblazers who helped mold local culture through sound, art, and dance with imagination and virtuosity. A powerful message as hip-hop celebrates its 50th anniversary.

As my visit winds down, Lopez and I are joined by Zard One, an original member of the Floor Masters. We’re seated in the gallery space across the hall, and I notice his fingertips are stained with paint. Thoughtful and soft-spoken, he’s an artist and lifelong friend of Mario’s.

The docents are making their rounds, turning off lights and securing items. It’s a signal that I’ve overstayed my welcome. But, before I head out, I ask them both what they hope visitors take with them.

Lopez is first to answer. “We have tours coming in from different schools that are interested. It’s [about] educating the kids,” he says.

PARTNER CONTENT

Just like hip-hop, the exhibit serves as a generational legacy. Each one teach one, as they say.

“It’s for the youth,” Zard One adds.