South Bay doesn’t draw attention to itself. Take Chula Vista, my hometown and the nation’s 78th largest city. Down-to-earth and decidedly unflashy, with nearly 280,000 residents, it’s bigger than Buffalo and will soon be home to more people than St. Louis. Yet it trundles quietly along, rarely grabbing headlines. It’s a major city dressed in the workaday clothes of a small town.

The other parts of South Bay share a similar humility. Imperial Beach doesn’t brag that an entire HBO series (John from Cincinnati) was set in its beachside neighborhoods, and Bonita—unlike, say, Poway—keeps mum about its backcountry flavor. Even the retired admirals in Coronado are too busy yachting to crow about the well-manicured lawns in their tidy community.

But if you know where to look, vibrant life and culture thrive here amid the Victorian homes and cookie-cutter McMansions. It’s been that way since the beginning, when the region started to attract fruit and vegetable farmers around the turn of the 20th century.

In 1909, a utopian commune called Little Landers drew dozens of people to San Ysidro by filling their heads with visions of an agrarian paradise. Everyone would work the land and leave their stressful jobs behind for natural beauty, poetry, and togetherness, the commune promised. As one early settler declared, “People want some sweetness and light in their lives!”

The Little Landers commune in San Ysidro

But the community’s motto came with some classic South Bay restraint: “A little land and a living, SURELY, is better than desperate struggle and wealth, POSSIBLY.” In other words, curb your enthusiasm.

Little Landers went belly-up, and it took decades until South Bay started to really take off during World War II. That’s when my grandparents and thousands of other locals flocked to build military aircraft at Chula Vista’s Rohr Industries (a B-24 bomber got named “Chula Vista” after a bond campaign). The Navy reclaimed tidelands on the Silver Strand to construct a military base, and lemon fields gave way to cozy suburban tracts.

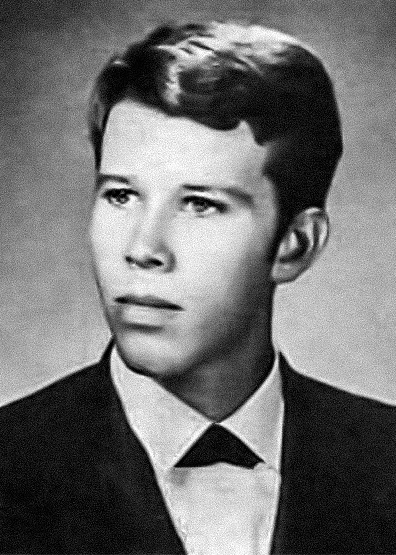

Around this time, South Bay produced a celebrity. Gravel-voiced musician Tom Waits went to high school in Chula Vista, singing about working at a National City restaurant in his song “The Ghosts of Saturday Night (After Hours At Napoleone’s Pizza House).” He also name-dropped his hometown in a tune called “Had Me a Girl,” growling, “Then I had me a girl in Chula Vista. I was in love with her sis-tah.”

So what’s South Bay like now? Things are definitely newer and nicer than they used to be, thanks to a 20,000-seat amphitheater and an elite athlete training center. There’s also a billion-dollar bayfront center in the works, and potentially a four-year university.

Eastlake, Chula Vista’s mammoth master-planned community, didn’t exist when I was a kid. It’s now a suburban paradise for those who like giant houses and good schools, including star professional wrestler Rey Mysterio. Meanwhile, National City’s sudsy “Mile of Bars” is long-gone, replaced by the auto dealerships along the Mile of Cars.

The San Ysidro border crossing is one of the busiest ports of entry in the world, and Imperial Beach is shedding its gritty image with new restaurants, condos, and even a $1.5 million renovation of its iconic pier.

As for the “Crown City” of Coronado, it is, as always, a boat shoe with its own zip code. But even this tidiest of towns has a hidden dark side: In the 1970s, a Coronado high school teacher and a bunch of beach bums created a $100 million marijuana-smuggling operation and dominated the drug trade until everything went awry.

These days, if you want to find South Bay characters like the ones Tom Waits loved to sing about, just drop by local mainstays like Lolita’s, Aunt Emma’s Pancakes, or his old haunt, Napoleone’s. Or visit the Lilliputian community of Lincoln Acres.

PARTNER CONTENT

Thanks to a quirk of municipal geography, Lincoln Acres is a tiny dot of unincorporated county land that’s entirely surrounded by National City. Things are done differently in “The Acres,” as locals call it: Residents have been known to walk goats down the streets on leashes, the local cemetery allows families to erect and maintain their own headstones, and the post office used to be open just two hours a day. “It’s a real trip,” one resident tells me. “It’s like a little Pleasantville.”

Uh-oh. He’s said too much. Gotta be modest around these parts about the good stuff. It’s the South Bay way.